Algorithms everywhere. Like, everywhere. We all know it. Our feeds are filled with them. You receive content specifically chosen for you by the machines. Behind the machines are people, at least in terms of those who developed the idea.

Kyle Chaykra begins his book Filterworld with the story of the Mechanical Turk.

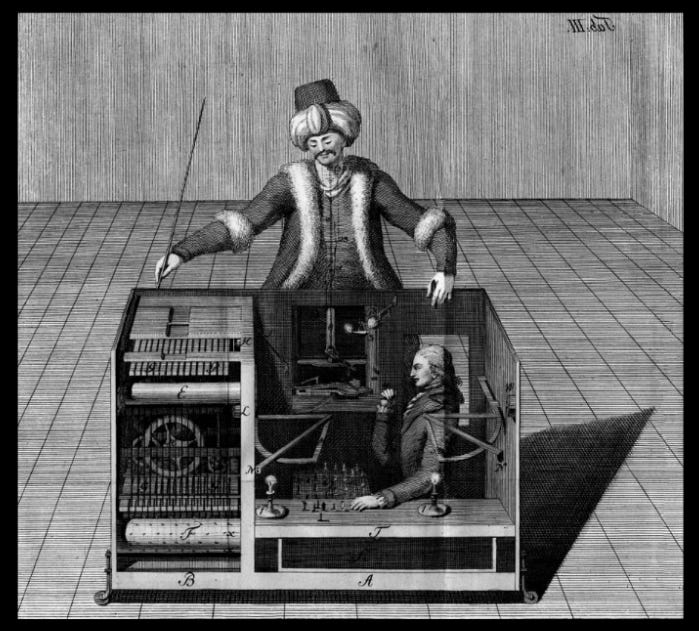

In 1769, a civil servant in the Habsburg Empire named Johann Wolfgang Ritter von Kempelen built a device nicknamed “the Mechanical Turk.” It was a gift created to impress the Habsburg empress, Maria Theresa of Austria. Von Kempelen’s nigh magical machine could play and win a game of chess against a human opponent simply by means of internal clockwork gears and belts. As seen in historical etchings, the Mechanical Turk was a large wooden cabinet, about four feet wide, two and a half feet deep, and three feet tall, with doors exposing the elaborate machinery inside. On top sat a humanoid automaton the size of a child, dressed in a robe and turban and sporting a dramatic mustache, leaning over a chessboard. (The Orientalist archetype seen from the European perspective conflated the foreign-human and the foreign-machine.) The Turk’s left arm hovered over the chessboard, grasped pieces, and moved them. The machine chimed when a move was made, detected when the other player cheated, and made various facial expressions. So befuddling was von Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk that it traveled internationally, matching up with the likes of Benjamin Franklin in 1783 and Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809. Both men lost.

He goes on to say that what no one could see was a secret compartment in which a world-class chess champion would sit. The machine wasn’t a machine after all, at least not a machine that could play chess.

The chess aficionado lives in your Instagram feed as well. He knows which YouTube videos you watch and he’s there to give you more and more and more. He’s there to keep you watching so he can sell more ads to companies you’re most likely to buy from.

Remember: it’s all an algorithm. Break the addiction before you go back, because the formulas want to keep your focus.